"Klaatu Barada Nikto"

This time of year offers excellent orographic clouds,

such as this lenticular cloud over Mt. San Jacinto.

First is a comparison of the size of our sun as it appears now, in January, and as it will appear in July.

The larger outline in the photo is the sun from January 3, when Earth is closest to the sun. This photo was overlaid on a photo from July, when the Earth is farther away. There's a noticeable difference in size.

Below is an exaggeration of the orbit and the orientation of Earth's pole. Perihelion and northern hemisphere winter is on the left; aphelion and northern hemisphere summer is on the left.

The Earth's tilt defines the orientation of the seasons, which I've added as a ring with zones based on which season the Earth is in during its orbit. Because of the elliptical orbit, Earth accelerates as it approaches perihelion and slows at aphelion. So, the Earth is closer to the sun at aphelion, but it also spend less time in this position. The reverse occurs in northern summer. Our Earth lingers in the summer position because it slows near aphelion.

Many people are aware of the sun being closer and farther away while not being aware that earth is speeding up and slowing down.

The longer winter for the southern hemisphere was an early hypothesis for why Antarctica is so cold.

Astrologers like to point to the sun's position and imagine it has some influence in our lives. I like to point to the sun's position and say it has some real scientific relevance. In this case, the astronomer's understanding of Earth's changing orbit is a foundation of the science of climatology.

This understanding has linked the motions of Earth's tilt with the changing shape and orientation of the Earth's orbit with the rise and fall of Earth's ice ages.

As the Earth's pole precesses, our seasons rotate:

While the pole is precessing, the points of perihelion and aphelion are moving in the opposite direction.

Astronomers refer to the rotation of the season as precession, which as has a cycle of almost 26,000 years. Climatologist are interested in a different cycle that combines the motion of the seasons with the motion of perihelion. They also call this "precession" and recognize a cycle that varies in length between 19,000 and 23,000 years.

Climbing to Venus. Below is a recent photo of Venus of Intersection Rock at Joshua Tree National Park. The exposure brings out the lights from climbers scaling the rock at dusk. Projecting their path along a rock points to Venus, a worthy goal.

I propose that Astronomy can help. It can calculate the best time for attempting a climb to Venus. Let's look at our planets.

We have 4 planets visible in the western sky at dusk..

Our Evening Planets

Of these, Mars and Venus will show significant movement against the background stars.

Venus, moving the most, will come closer to Earth and change in apparent size. Now is a good time to watch and photograph Venus, aided by the high tilt of the ecliptic at this time of year. This photo shows relative sizes of Mars, Venus now, and Venus in one month if you looked through each with a telescope at more that 100x magnification. (Note that this is size and not position, so you won't be able to see these objects together through a telescope.)

In about one month, Venus will be closer, and because of the growth of the crescent shape, it will be easier to hang on to.

Just to make sure, this is a joke.

By February 1, the crescent moon joins the bright planets in the evening sky. If you can grab the moon and hang on, it will take you to Jupiter (also a joke).

Jupiter offers a few worthwhile transits, depending on whether you a day job:

Now, a look at the deep sky

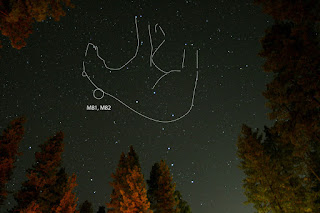

Orion, redrawn as a climber.

Orion the Climber seems plausible, as it would explain this photo:

Of course, another explanation of this photo is what you get when you put a $1000 camera on a 5-dollar tripod.

jg

No comments:

Post a Comment